The man who met the Báb

The man who met the Báb

Some new facts about his life

by Brendan McNamara

In 1930, Shoghi Effendi asked George Townshend to pen an introduction to a translation he was working on of Nabil’s history of the early days of the Faith, a volume he was planning to publish in the West. The request came in the course of a fascinating correspondence (communications back and forth between the World Centre of the Faith and Mr Townshend’s home in rural west Co. Galway), during which the Guardian elicited Mr Townshend’s opinion on the content and style of the manuscript in preparation. Though thrilled to his core by the exploits of the early martyrs and saints, the heroic and tragic life of the young Manifestation of God, Mr Townshend proffered the view that the time was not opportune for the publication of Nabil’s account. He explained that he did not feel the general public would be interested (perhaps not even the Bahá’ís themselves), that the narrative could be seen as “an unedifying story of cruelties and local fanaticism, and would be a misleading introduction to the revelation of Bahá’u’lláh.”1 He stepped back from a definitive negative conclusion by offering the view that if, as Shoghi Effendi intended, an introduction with sufficient contextual background information were included then, “Bahá’í students and other readers of oriental history and literature would welcome the book.”2 It was George Townshend himself whom the Guardian had in mind to pen such an introduction.

Having taken on the task, though feeling inadequate and humbled by the trust imposed in him by his Guardian, George Townshend set to work and outlined a plan of work for his assignment. Aided by a profusion of material and suggestions provided by Shoghi Effendi, Mr Townshend began ordering his thoughts and imagining the piece he was creating. He identified the key information the introduction must include and, in particular, “seized upon the episode of Dr Cormick”.3 This “English physician, long resident in Tabriz”4 was the sole Westerner known to have met and conversed with the Báb, and the doctor’s brief but revealing account of his encounters with the young Prisoner (first published by the orientalist E.G. Browne), seemed to Mr Townshend to be of great significance and potentially of much interest to people in the West.5 The introduction completed, the Guardian asked Mr Townshend to suggest a title for the volume, which until then had the working designation, “Idylls of the Immortals: Nabil’s Narrative of the Early Days of the Bahá’í Revelation”. After one abandoned attempt, George Townshend suggested, and the Guardian accepted, that the first part be replaced by “The Dawn-Breakers”, an inspired title of a book that has come to be regarded as irreplaceable, a much loved treasure in the pantheon of Bahá’í literature.

But what is known of the physician “long resident in Tabriz” who had this singular and, by all accounts, unique encounter with a Manifestation of God, the only Westerner to have met the Báb? Apart from his own brief account of the events surrounding his experiences, little was actually known of him. In a collection of contemporary Western accounts of the Bábí and Bahá’í religions from 1844–1944 (first published in 1981), Moojan Momen included a short biographical note on the doctor which uncovered the interesting detail that he was the son of an Irish physician attached to the court of the royal family at Tabriz. The profile relates that William Cormick was born in Tabriz in 1820, was sent to England to study medicine and, on his return to Persia in 1844, was appointed as physician to the British Mission in Tehran. He later accompanied the Crown-Prince, Nasiru’l-Din Mirza, to Tabriz on the Prince’s appointment as Governor of the province of Adhirbayjan. The note begins by identifying the Cormick seat in Ireland as Co. Tipperary and ends by recording William Cormick’s demise and interment in Tabriz in 1877. Since the publication of this short biography more information has come to light which clarifies the beginning and the end of the doctor’s fascinating life.6

An English physician

The fact that William Cormick first appears in history as an “English” physician, and the designation thereafter followed him in the accounts of this time, is not surprising. The question of identity, religion and Empire, with respect to people of Irish background, is convoluted and complex. For the doctor’s father, leaving his homestead in rural Ireland in the late 1700’s to make his life at the heart of the Empire in London and thereafter in service its international activities as a surgeon, being Catholic and Irish would not have advanced his ambitions. There is ample evidence of a chameleon like self-identification on the part of Irish people abroad in the British foreign-service, for pragmatic reasons, as in the case of the Queen’s Minister in Persia at the time of the Báb, Sir Justin Sheil and his wife, Lady Mary, who presented themselves as “English” but were in fact Irish.7 For his part, Dr William Cormick was born in Tabriz, his mother was Armenian and, though his father was Irish, we could correctly say that his was an identity of many shades and particularities! Unlike the Sheils, who were very overtly followers of the Catholic faith, Dr Cormick senior does not seem to have been too attached to the religion of his birth. He was married by a Protestant Minister in 1812 and thereafter the family’s orientation, from the perspective of religion, seems to have been Protestant. In any event, Dr Cormick’s background and education ensured that he was regarded by the expatriate community as either ‘English’ or simply ‘European’,8 and though evidently fluent in Farsi, he was similarly regarded by the local Persian population.9

Much of the fascinating detail concerning Dr Cormick’s Irish heritage was unearthed by an intrepid researcher, Vincent Flannery, who traced the family’s Irish origins to his own home county of Kilkenny, on the borders of Co. Tipperary but very definitely on the Kilkenny side.10 Cussane, Tullahought, the location for the Cormick homestead, is not far from Carrick-on-Suir (in Co. Tipperary) and though “the original Cormick dwelling house no longer stands… its position is clearly seen by its remains.”11 Vincent traced a distant relative of Dr Cormick to Galway city. This old gentleman had written about his cousin’s exploits in service to the royal family in Tabriz, an article which appeared in The Old Kilkenny Review in the year 1996 and which included a photograph of the doctor replete with oriental fez and wearing two royal decorations on his jacket.12 The photograph was a precious ‘find’ indeed! Now we could see what he looked like, the man who met the Báb.

Royal appointment

Dr Cormick began his Persian medical career attached to the British Mission in Tehran in the year 1844 when the Minister in residence was Justin Sheil from Co. Kilkenny.13 Two years later, as his father before him, “he was seconded as physician to the family of Abbas Mirza, and later to the Crown Prince, Nasir al-Din Mirza”.14 In March 1847, the Crown Prince was appointed Governor of Adhirbayjan and Dr Cormick joined the royal party that decamped to the provincial capital at Tabriz. It was at this very time that the Báb, now in the clutches of the scheming Prime Minister Haji Mirza Aqasi, was prevented from proceeding to Tehran for a proposed meeting with the Sovereign and was taken instead as a captive to Tabriz. The arrival of the Báb in that city created a great stir, something the doctor must have been aware of even if he could not imagine that he himself would be drawn into the centre of the drama.15

After some days in Tabriz the Báb was incarcerated in the remote castle of Makú.16 The following April the Prime Minister, concerned at the increasing influence the Prisoner was exerting over the people of the area (in effect his ‘own’ people as he had been born in Makú), transferred the Báb to another fortress prison, this time in Chihriq.17 Even from this remote outpost the influence of the Personality of the Báb and of His teachings only increased and “Siyyids of distinguished merit, eminent ulamas, and even government officials were boldly and rapidly espousing the Cause of the Prisoner”.18

The authorities in Tehran reacted by sending the Báb to Tabriz so that these matters could be further investigated. His return to the provincial capital only served to fuel the enthusiasm of the people of the city who joyously welcomed the Báb and, despite threats and entreaties, strained to get a glimpse of this famous Prisoner. On being apprised of this tumult, the Prime Minister ordered the ecclesiastical dignitaries of Tabriz to meet immediately to consider how to “extinguish the flames of so devouring a conflagration”.19 The interrogation of the Báb by the clerical authorities which followed, in the presence of the Crown Prince of the realm, was a supremely dramatic affair. Rather than succeed in humiliating the young Shirazi, as they deliberated on the steps to be taken to stamp out His nascent religion, the authorities presented the Báb with an opportunity to openly declare His station, which He did in a statement that electrified the convocation, totally perplexed His accusers and lead to the dispersal of that meeting, the delegates “confused, divided among themselves, bitterly resentful and humiliated through their failure to achieve their purpose”.20 The only decision the authorities could agree on was to inflict on Him the torture of the bastinado, before returning Him to Chihriq.21

Finding a place in history

The account left to us by Dr Cormick throws more light on these startling happenings and introduces his part in these events.22 He tells us that as part of the process of the Báb’s arraignment, he and two other Persian doctors were sent to examine Him to determine whether He was of “sane mind, or merely a madman, to decide the question whether to put him to death or not.” The Báb was loth to answer the doctor’s questions, except when Dr Cormick averred that he would like to know something about the Báb’s religion, as, not being a Muslim, he might “be inclined to adopt it”. “He regarded me very intently on my saying this”, Dr Cormick wrote, “and replied that he had no doubt of all Europeans coming over to his religion” The report of the three doctors was “of a nature to spare his life” though Dr Cormick goes on to mention that the Báb was put to death sometime later. But his involvement does not end there. According to the Dr Cormick, during the administration of the bastinado, which took place after receipt of the examining doctors report, the Báb was struck on the face, a blow “which produced a great wound and swelling of the face.” On being asked whether He wished a doctor to attend His wound, the Báb specifically asked for Dr Cormick who “accordingly treated him for a few days”. The doctor complained that he was unable to have a “confidential chat” with the Báb on any of these occasions as Government people were always present. The account concludes,

He was very thankful for my attentions to him. He was a very mild and delicate-looking man, rather small in stature and very fair for a Persian, with a melodious soft voice, which struck me much. Being a Sayyid, he was dressed in the habit of that sect, as were also his two companions. In fact his whole look and deportment went far to dispose one in his favour. Of his doctrine I heard nothing from his own lips, although the idea was that there existed in his religion a certain approach to Christianity. He was seen by some Armenian carpenters, who were sent to make some repairs to his prison, reading the Bible, and he took no pains to conceal it, but on the contrary told them of it. Most assuredly the Mussulman fanaticism does not exist in his religion, as applied to Christians, nor is there that restraint of females that now exists.

In commenting on the interaction between Dr Cormick and the Báb, David Hofman draws a parallel with the biblical figure of Zacchaeus, who climbed a tree to glimpse the Nazarene as He passed by and was called to Jesus’ presence, a circumstance that assured his fame for all eternity.23 It is the story of an unwitting outsider thrust centre stage for the briefest of moments and though not fully aware of what is going on, nonetheless achieves a place in history because the Person who drew him to Himself was none other than the Manifestation of God. Dr Cormick cleaned and dressed, on more than one occasion, the wound upon the face of the Representative of God on earth and so ensured that the name of ‘Cormick’ will be recorded in the annals of religious history for all time. There is no evidence that the good doctor thought much or spoke of these events again, apart from his one brief, revealing, account contained in a letter to a friend. Some new facts about his life thereafter have, though, only recently come to light.

New facts

In March of 2011, Vincent Flannery’s research on Dr William Cormick, which had appeared previously in a slim volume of essays on early links between the Bahá’í Faith and Ireland, was posted on the world-wide web.24 Within a few days a message was received on the website’s notice board from Mrs Vicky Uffindell of Hertfordshire in England. Mrs Uffindell is the great-grand daughter of Dr William Cormick. Having investigated her family history for the past thirty years, she shared some very interesting information from her research and confided that she herself had only become aware of her antecedent’s connection with the Báb a few years previously. Mrs Uffindell discovered that William was actually born on July 19th in 1819. He and his brother, John, were brought to England in 1829, left in the care of family friends and sent to school. William’s medical training began in 1836 when he was apprenticed to an apothecary in Lewes in Sussex. There is no evidence of a visit to Ireland from around this period, but there is a record of William and his brother John meeting up with Irish relatives in Waterford in June 1841.25 This fact is included in the testimony of John Cormack, of Cussane, Tullaghought, writing from Australia in the year 1880. It is of interest as it confirms contact between the Irish and Persian Cormick’s and also indicates how the name underwent adaptation so that Cormick and Cormack became somewhat interchangeable.

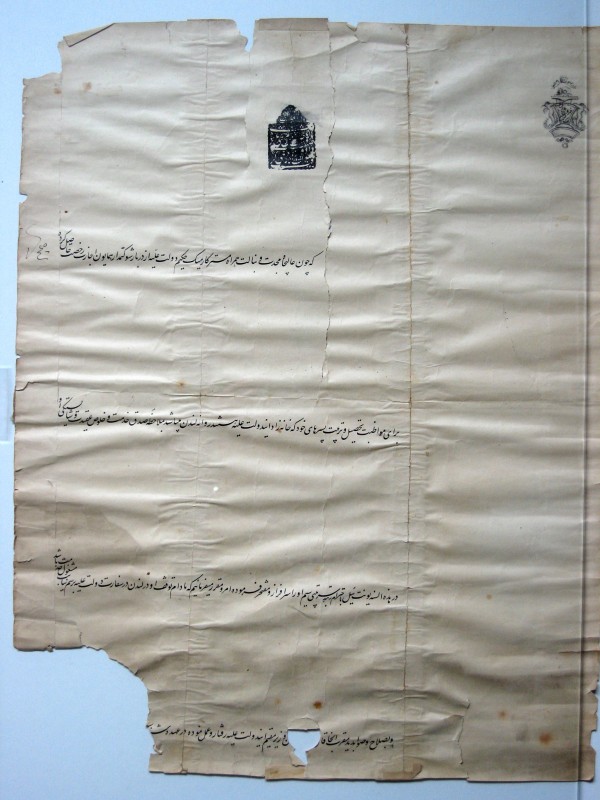

Mrs Uffindell gave details of William’s marriage to Tamar Daoudian, the daughter of Daoud Khan (a general in the Persian army), in October 1850. Of the twelve children born to William and Tamar, seven died before the year 1871 and all were most likely interred in the Armenian cemetery in Tabriz where it is known there are eleven Cormick family graves.26 William died on the 30th of December in 1877, aged 58, and it was thought that he too was buried in that place.27 However, we now know that William, Tamar and their five surviving children did in fact leave Persia to set up home in London in the year 1873, at one time settling in Regents Park and latterly in Hammersmith. During the family’s time in London, William was given permission by the Queen to accept and wear the insignia of the Order of the Lion and the Sun (2nd Class) bestowed upon him by the Persian government. He also received a ‘firman’ from Persia, appointing him as attaché to the Persian Legation in London and bestowing upon him the title of ‘Satrib’.28 When Dr Cormick died he was buried in one of London’s great burial grounds at Kensal Green.29

Mrs Uffindell’s grandfather was William’s son, George Cormick. He in turn qualified as a physician and returned to work in Persia around the year 1890. George married an Armenian lady, Melanie Enikoloffian (the daughter of a colonel in the Persian army), and they had eight children. Following George’s death in Sultanabad in 1919, the family returned to England. One of George’s children, Sophie (d.1990), was Mrs Uffindell’s mother.

Conclusion

Perhaps, we now know as much as we can possibly discover about Dr William Cormick. More may come to light in the future and all will, no doubt, be parsed and sifted through, even the smallest of details. What of the links, for example, between the Cormick family and the Armenian community in Tabriz? Dr Cormick’s father, John, was married to an Armenian Christian woman, Shireen, and William’s wife, Tamar, was also from this background.30 Of particular interest here is that Tamar’s father, Daoud Khan, was a general in the Persian Army. Another Armenian officer figures largely in the story of the Báb, namely Sam Khan, the officer in charge of the regiment that was called on to execute the Báb.31 Sam Khan was released from a duty he had no heart for, in the most mysterious of circumstances. Is it possible that the Cormicks knew him? Could they have heard from him the details of that most extraordinary day when the Báb was suspended in the town square of the city in order to be done to death?

We may never know. The story of the doctor “long resident in Tabriz” will surely, though, be the subject of further research, maybe even of songs and poems; indeed that has already been the case! In his poem, ‘Dr Cormick Decides’ , included in a collection published in 1979, Roger White imagines Dr Cormick conversing with himself one morning as he ponders on which cravat to wear.32 In the poem the doctor recounts his brief encounter and in the last few lines the poet has the doctor posit, concerning the Báb,

One wonders what might become of such a fellow.

Perhaps, of course, it’s just another tempest in a teapot.

At this stage we can certainly say that this has proven not to be the case. And we can further confidently predict that, over time, people will want to know as much as they possibly can about the man who met the Báb.

- David Hofman, George Townshend, George Ronald: Oxford, 1983, p.65. The full story of this most interesting correspondence is carried in chapter 6.

- Ibid. p.66.

- Ibid. p.67.

- Ibid. p.67.

- Ibid. Browne himself thought the episode of Dr Cormick was of special significance for similar reasons. See, Edward Granville Brown, Materials for Study of the Bábí Religion, University Press: Cambridge, 1918, pp.260—262.

- Moojan Momen, The Bábí and Bahá’í Religions, 1844—1944: Some Contemporary Western Accounts, George Ronald: Oxford, 1981, p.497—498.

- This issue is dealt with at length in Brendan McNamara, “An Irishwoman in Tehran, 1848–1853: Identity, Religion and Empire”, forthcoming (2012) in proceedings of Erin/Iran Conference, UCC, 22/10/2011. (webmaster’s note: there is a YoutTube video of Brendan delivering this talk here.)

- Vincent Flannery, “Dr William Cormick”, in, Connections: Essays and Notes on Early Links Between the Bahá’í Faith and Ireland, Brendan Mc Namara (Ed.), Tusker Keyes: Cork, 2007, p.19.

- For example, Dr Cormick was prevented from taking up the position of personal physician to the newly crowned Nasiru’l-Din Shah, as the Prime Minister wanted to stymie any British (and indeed Russian) influence so close to the throne. He was, therefore, replaced by the unfortunate Frenchman, Cloquet. See, Momen, p.497. According to Williams’ great-granddaughter, William helped with translation at the British mission, (personal communication). It should be noted that all mentioned could accurately be designated ‘British’, given that Ireland was part of the Empire at that time, but their self-identification was clearly ‘English’ which raises interesting questions.

- Vincent Flannery, p.1—20.

- Ibid. p.4.

- Ibid. p.9.

- Brendan Mc Namara, “Lady Mary”, in, Connections: Essays and Notes on Early Links Between the Bahá’í Faith and Ireland, Brendan Mc Namara (Ed.), Tusker Keyes: Cork, 2007, p.24.

- Flannery, p.8.

- Ibid. p.10.

- Shoghi Effendi (1), The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl’s Narrative of the Early Days of the Bahá’í Revelation, Bahá’í Publishing Trust: Chicago, 1932, p.223—243.

- Shoghi Effendi (2), God Passes By, Bahá’í Publishing Trust: Chicago, 1944, p.19. Details of Haji Mirza Aqasi’s birthplace can be found in, Momen, p.154 (footnote).

- Ibid. p.20.

- Ibid. p.21.

- Ibid. p.22. Shoghi Effendi’s account of this event is truly marvellous and only a brief part is contained here.

- The bastinado involves the beating of the upraised soles of the feet with a rod.

- Dr Cormick’s account is cited in, Brown, p.260—262, Momen, p.75, Flannery, p.12—13 and Shoghi Effendi (1), p.320—321 (Footnote). All quotations in this section are from this citation.

- Hofman, p.64.

- Webmaster’s note: That’s here! The article mentioned is this one.

- At the Adelphi Hotel, now the Tower Hotel. All information in this section is from personal communications with Mrs Vicky Uffindell unless stated.

- Flannery, p.20.

- Ibid.

- A notice of the awards appeared in the London Gazette, 12/10/1875. A firman is a royal decree and this particular firman is in the possession of Mrs Uffindell.

- Square 63 (Path Side, number 26270). See picture.

- Married October 19th, 1850. Information from Mrs Uffindell.

- Shoghi Effendi (1), p.510—515.

- Roger White, “Dr Cormick Decides”, in Another Song, Another Season: Poems and Portrayals, George Ronald: Oxford, 1979, p.77—79.

No comments:

Post a Comment